By Allison Schuette

To fix something, one must first see it as broken.

To heal something, one must first learn to see.

You thought you learned a thing or two about healing when, in your 20s and diagnosed with Graves disease, you swore off Western medicine in favor of working with an alternative practitioner. You felt more certain you’d learned a thing or two when, to your surprise, the healing brought about a broader transformation, a release from oppositional thinking. Where previously you had seen in Western medicine a patriarchy that tortured the living, dynamic body into the metaphor of a machine, you began to see an additional practice that could work alongside alternative methods. You saw that you could risk engaging a world still in need of its own transformation. You didn’t need a fix for patriarchy before you entered the fray.

All this is true, and you find, even so, that you might know more about fixing than healing, or rather the desire to fix since fixing itself is an illusion, a seductive one with promises of perpetual safety, fairness, well-being. In fact, there were days—of racing heartbeat, of arrhythmia, of weight loss, of goiter, of emotional roller coasters—when you wanted nothing more than a fix, a return to the body before the onset of Graves disease. And twenty years later, after radiated iodine treatment, synthetic hormones and ongoing health insurance to cover costs, you have more or less fixed GD. But, of course, one fix is not a fix for all seasons—ask any addict.

And, so, on the campus where you teach, you join with your partner in starting a story collection and facilitation practice. You interview students and faculty and staff about their experiences with belonging and not belonging. You edit the interviews into stories that you use in classrooms, presentations, and workshops to help people reflect on what it takes to live well together. The stories, especially those of harassment and exclusion, draw you out into the community, the city where you live, a city once known in the region as a sundown town. You discover an underlying story between your county, Porter County, and the one next door, Lake County, home to Gary, Indiana. It’s a story of redlining, restrictive covenants, and white flight; a story of civil rights, the push for open housing, and the first election of a black mayor; a story of automation and layoffs at the mills, of suburbanization, and the erosion of Gary’s tax base. You broaden the reach of your story collection. You believe that there’s an overarching story here, which if heard, will free everyone to live differently.

To fix is to pin down, to hold in place, to render immobile.

To heal is to cross your legs on the cushion, to make room, to unfurl.

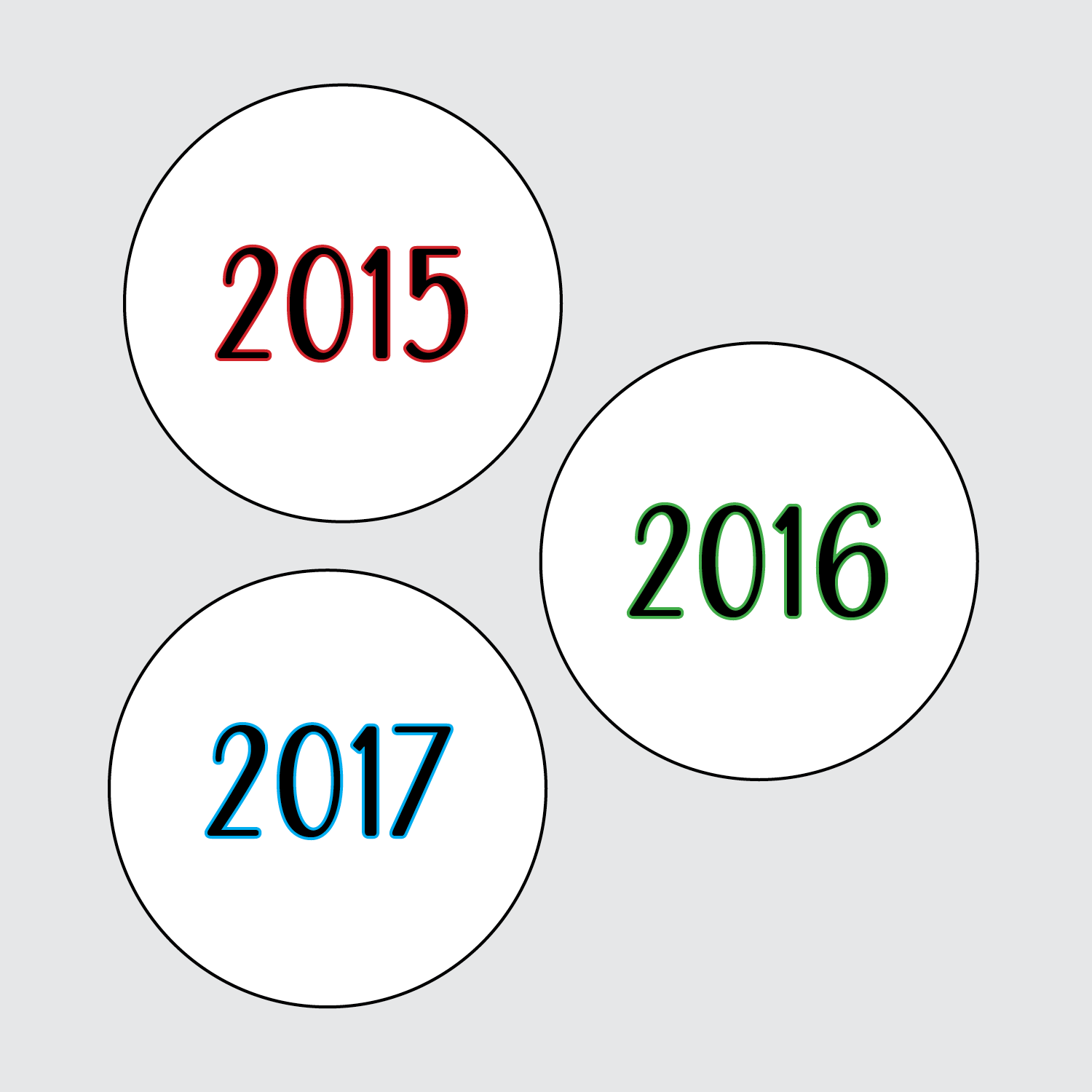

Through research, you develop a picture of the legacy of a sundown town. In 1960, your city’s population was 99.8% white. In 1980, 97.7%. In 1990, 98%. In 2000, 94.4%. This final figure at a time when the country reported a population only 77.1% white and Lake County next door 60% white. Maybe African Americans no longer have to leave by sundown, but they certainly aren’t being invited to stay. In fact, you further learn that a series of cross burnings in the late ‘90s prompted a colleague to start a research center to track bias incidents in the region. When the center studied newspaper reports from 1990-2014, they found over twice as many bias incidents occurred in your city than in any other single city or town in Lake and Porter counties, most of them racially motivated.

In 2010, your city’s population is 89.9% white, but increasing diversity is no panacea. You interview a young black alumnus in 2015 about his arrest, an arrest, eventually dropped, that fit the national profile too closely for comfort. The dash cam, at least the excerpt shared on YouTube and widely over social media, portrayed a black man talking back to the police, refusing to take his hands out of his pockets. It showed him being pushed up against the cruiser and handcuffed. Full footage, not publicly shared, showed a more complicated story. Two cars pulling over one SUV. The voice of a young man greeting the officer at his window. An officer ordering the young man to “Come here” in a way that to the young man sounded like a command given to a dog.

He reaches for me, like he was pulling me away from the camera. Why would he do that? Why wouldn’t he want to be in the camera for his own safety? He’s touching me, pulling me, and I pull away. “I’m coming. I can’t come any faster.” He asks if I have an ID. I say, “Yes, it’s in the car.” He tells me to go get it. Absolutely that wasn’t going to happen. I didn’t feel like I should go back. There were four police cars by the time I got out of my car. I felt outnumbered. I wanted to see my mom again. I wanted my friends to be safe. I didn’t have a good feeling about turning my back on four police cars in light of everything that’s going on. I was looking out for myself. I just didn’t know what was going to happen next. I mean, I never even expected to be out of the car, I didn’t know why I was. I never would have expected to get shot either, but why wouldn’t that also happen given the way things had gone?

The interview helps him prepare his story for the city’s Human Relations Council, which decides to publish a statement condemning the arrest. When they hold a meeting to discuss that statement, the Fraternal Order of Police shows up en masse in their uniforms with their guns. They harangue the members of the HRC and intimidate community members, interrupting them when they take to the podium. One black resident reports feeling safer in Gary where she grew up than on the streets of your city. An elderly white man standing behind you—part of a self-elected, two-person peanut gallery—audibly scoffs. For him, the streets of your city are the safest place in the world. White people can’t be dangerous because they have never represented danger to him. He cannot imagine how, even now, he is himself the danger.

To fix is to try to return to what once was.

To heal is to recognize there has never been a “once.”

It hits you one day that you believe you’re responsible for ending racism in Northwest Indiana. The insight arises during an online meeting of your bodhisattva training group. Further: if through research, you somehow understand all the factors that contributed to racial and economic injustice in the region, you can end racism in the past as well as the present, undo history, wrench the moral arm of the universe back through time, a bodhisattva superhero pinning an arch nemesis to the ground. You laugh out loud at the absurdity of the claim, at the way you imagine more power for yourself than you actually have. The fix is in. You see it now, your red hands caught controlling outcomes.

Turns out a bodhisattva cannot end suffering. The world of causes and conditions, the world of samsara, is dynamic and fluid. It cannot be fixed. That’s why the first noble truth in Buddhism is that suffering exists. With all that roiling, with the innumerable causes and conditions that have preceded us, that are present now, that continue on into the future, we are bound to hurt ourselves and each other, and often with inequity. Reality is given, fundamental, foundational. It is the ground with which you must work. You have no choice in the matter, only in the encounter. Your nobility lies in your acceptance of that-which-is rather than that-which-you-want-to-be.

To those taught that with enough perseverance and labor, they can shape the world to their will, this insistence that you must accept that-which-is infuriates. You cannot read acceptance as anything other than capitulation, a giving up which is a giving in, a passive resignation. For what is healing that cannot cure illness? What is love that cannot uproot injustice? The options seem stark: be the savior or be the victim. But this is a false dichotomy. If you cannot control outcomes, it isn’t because someone else is doing so in your place, but because no one can. That-which-is is really that-which-is-unfolding-always-already.

Graves disease has no cure, but its presence isn’t therefore immutable. Injustice has no cure, but its inevitability is no less dynamic. A bodhisattva engages a world still in need of its own transformation, in part because a bodhisattva allows illness and injustice to touch her and in the process is herself transformed. Make no bones about it. Being touched by pain is unnerving. It leaves no room for security. Most of us are not used to walking on water, but in a world always already unfolding, we’d better learn to practice.

Allison Schuette (MFA Penn State / Creative Nonfiction) is a writer interested in documenting lives through text and audio in a variety of genres. Her written work has appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, Gulf Coast Review, Mid-American Review, and other journals. An Associate Professor in the English Department at Valparaiso University, she also co-directs the Welcome Project, an online, digital story collection used to foster conversations about community life and civic engagement. Their most recent initiative, Flight Paths, explores the history and unfolding of white flight as well as black empowerment in Gary and Northwest Indiana. Follow it on Facebook. Eventually, it will be a multimedia initiative to help participants, both regionally and nationally, engage and analyze factors contributing to de-urbanization and the fracturing of neighborhoods, communities, and regions in post-industrial America through the specific example of Gary, Indiana.